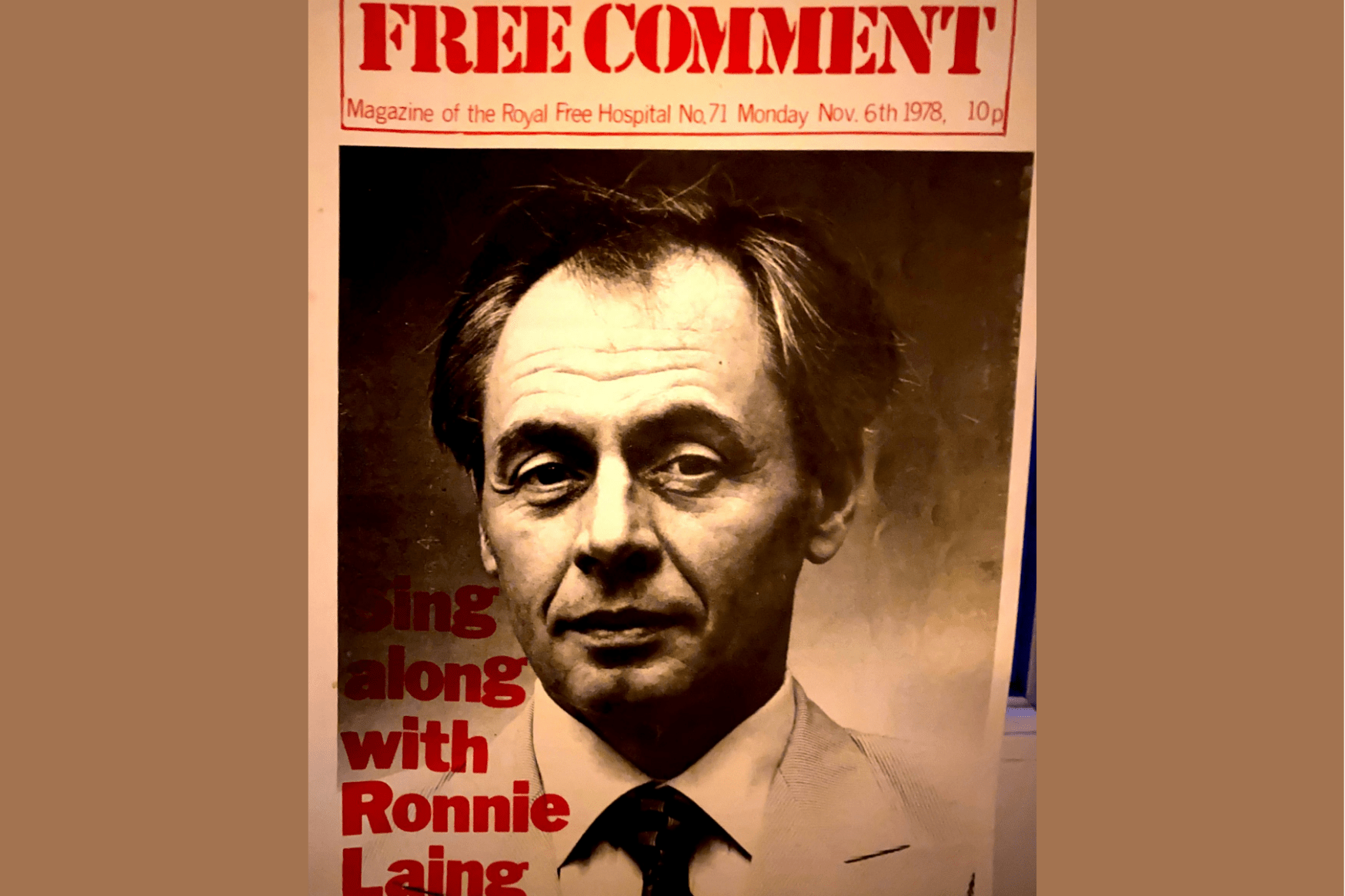

While decluttering during COVID I came across some wonderful memories which I want to share here. I interviewed the psychiatrist R.D. Laing in 1978 as a medical student at the Royal Free Hospital with my colleague Chris Sinclair. We co-edited with others a medical student magazine, “Free Comment”. This was a marvellous distraction from medical studies and involved every stage of writing and editing the material, pasting it up for printing, and selling the magazine. R.D. Laing was a psychiatrist who focussed on the experiences of people with psychosis. I was aged about 22 and very naïve. I had just completed a intercalated degree in psychology at the wonderful Bedford College in Regent’s Park and was already interested in training in psychiatry. I was especially inspired by Anthony Clare’s book “Psychiatry in Dissent”.

How I would loved to interview R.D. Laing now! There are several areas where I have developed overlapping interests to Laing, which I’d have liked to discuss with him. For example he was interested in Therapeutic Communities for people with psychosis and founded the Philadelphia Association. I have, with colleagues, tried to develop a therapeutic community for our anxiety disorders residential unit which is based on Compassion Focussed and Contextual Behavioural Therapies. Second, Laing was interested in the nature of the self. He argued in his book The Divided Self that psychosis occurs when there is tension between our authentic, private self, and the other false, rational self that we present to the world. In my own work I am interested in the nature of over-valued ideas, which, I argue, are derived from idealised values. I suggest these have developed into such an over-riding importance and rigidity that they totally define the ‘self’ or identity of the individual. Thirdly, he was interested in using psychedelic assisted psychotherapy. If I could raise the funds, I would love to investigate the role of psilocybin in OCD and BDD. Lastly he was fascinated by death and existentialism. I have co-authored with Rachel Menzies a book on overcoming fears of death and existential anxiety to be published in 2022.

I was ever the opportunist to get an interview. At the time R.D. Laing was promoting the release of an album of his poetry, Life before Death. His consulting room was very close to the Royal Free Hospital, I think, in Belsize Grove. I’ve not yet found the cassette recording of our interview, but here is the article in full. In those days, we didn’t think of asking for a selfie!

Latent discophrenics Chris Sinclair & David Veale risk “Life Before Death” with Dr R.D. Laing.

Staring vacantly at you, eyeless, on the cover of his recent album is a picture of R.D. Laing.

Laing, you see is disillusioned. His pessimism is not only limited to psychiatry; even life itself is threatened: “It’s a question of Morality; if we brutally and callously destroy our environment, and show no consideration for it, we’ll bite the hand that feeds us… if we destroy our ecosystem, we destroy ourselves, and it’s clear at the moment that we’re destroying our ecosystem. It’s a question of whether we’ll stop.”

Laing, however, is obviously determined to die with his boots on, and so, in order to increase his experience (and presumably ours), he has just made a record: “Life Before Death” Charisma Records, CAS II4I. He sees no incongruity in a psychiatrist producing a record: “I don’t think it’s as big a jump as all that: quite a few musicians have written well, not exclusively on music” but “I’m still using words”.

And so he is. The record consists of spoken sonnets laid over a Godspell-like musical background. Important questions are asked: “Are we aware we can’t remember who/we are? Does it require great fortitude/To live ataxic and aphasic through?/An anaesthetised decrepitude?” Like all pertinent Questions-masters, wise Ronnie leaves us to find the answers.

The New Medical Express (who must be the cleverest bunch of dicks around) have solved the problem by diagnosing mild discophrenia. Still, we can’t help sharing their hope that patient Ronnie won’t regress into a fully-fledged dischosis. Laing however, when we saw him, was well on the way to recovery and felt it was unlikely that he would be committed to the recording studios again.

“Amnesia not being a symptom of discophrenia, Laing still retains his intense anti-psychiatry feelings; that, in fact, conventional psychiatric intervention actually worsens a patient’s condition: ‘Biorhythm’ (in psychotic patients) is always swinging all around; they might be sleeping all day long and turning night into day: it practically always happens. Put someone like that into a psychiatric unit where everything is regimented. Time is regulated. You have to sleep at night and get up at the right time and be awake; and the way you conduct yourself; you’re not allowed to run backwards and forwards in the day-rooms for an afternoon; you get an injection; you’re certainly not allowed to jump up and down for an afternoon; you get an injection; you’re certainly not allowed to curl up in a ball in the corner in the middle of the afternoon. Well, I thought preventing people from doing these things which they are drawn to was actually driving them more crazy than they were.”

Laing’s answer was the Philadelphia Association. Treated with “in-difference” by orthodox psychiatrists, the Association is a charity whose members, students and friends are concerned to develop appropriate human responses to those of us who are distracted and made frantic by misery, which in our present state of knowledge is not mitigated, or is sometimes aggravated, by most forms of psychiatric intervention. It provides eight houses where “ten to fifteen people can stay in a place, and maybe a couple of more together people; but they would not be controlling them; they wouldn’t be acting as wardens.” It works; the statistics show that; and its ten times cheaper; yet only a few psychiatric consultants would ever consider sending a patient there.

Laing considers that medical education teaches doctors not to have “this” relationship, but to have “that” relationship with their patients. Acknowledging the need for a human approach to all branches of medicine, he denies the need for a personal relationship with a physician or surgeon: “I’d be just as glad for a machine to take my appendix out” Laing remarks dryly.

Psychiatry is different. Often “the cardinal symptoms of the illness is that humans are cut off from other people personally: a sort of lack of emotional rapport”. Using “that” approach nearly always fails in these cases; no organic cause can be found, and the patient remains frantic, scared stiff, literally frozen stiff with fear. “Now, the relationship that one is taught to have as a doctor is not the appropriate response in that situation: it is not one that puts a person, as a person, at ease with you as a person.”

Only when psychotherapy (as opposed to ECT, drugs, etc.) is used, is there any chance of their growing out, ceasing to be frightened of, and forming human bonds with, you: “Now, how is that going to happen; not easily in a psychiatric unit” comments Laing.

In the sixties, Laing was labelled as cult figure by the media. Laing himself was not too appreciative: “The stuff that was written about R.D. Laing was very remote… on a number of occasions they were almost scary…several times I even committed suicide….”

Part of this cult centred around the use of LSD. What does Laing think about it now, after the 1973 ban on its use? “I wouldn’t advocate its use publicly, but if I was asked to go on a committee of inquiry, I would argue the case strongly for LSD to be available to, um, some sub-set of doctors.”

Where does all this leave Laing now. Like some other famous psychiatrists in the past, he has moved away from his earlier, more clinically orientated work, to what is almost a metapsychology, examining psychology at large (and characteristically becoming increasingly disillusioned and pessimistic about it).

His early work is examined at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels, which is one good reason to study some of it. It would be a great pity to stop there however, for there is little doubt that Laing’s work has a significance far greater than something to pass exams with.

A post-script

R.D Laing died in 1989. I am not convinced that he was right that it was better to leave psychotic patients to their own “bio-rhythm”. What we know is that if you are not in sync with a Zeitgeber like sunlight and social rhythms of meals, then one’s mental disorder is likely to get worse and be more distressing. A good sleep routine and structure is important in regulating one’s affect and psychosis.

Psychiatry gets it that being on an acute inpatient ward is a last resort, and it’s now extremely difficult to be admitted unless one is very unwell or at risk of suicide or harming others. What would Laing have made of psychotherapies like CBT for psychosis? This might be offered when a patient is more stabilised. The focus in CBT in psychosis (I am not an expert in this area) is on trying to find the meaning of psychotic experiences, and emotionally processing past traumas. I think he would have approved.