By David Veale and Venetia Mitchell

In our previous blog we introduced the gut microbiota and its relationship to disorders in mood. We provided pointers as to how we can alter the health of our gut microbiota to support mental health.

This blog about microbiota-gut-brain axis is designed to provide understanding of the science behind how our gut may influence our mood. We look at various pathways to explain how our gut microbiota influences the brain and vice versa.

The majority of the science explaining these interconnected relationships is based on animal models. It is clear however, that human gut microbiota also influences the brain.

We hope by reading this blog, you understand how healthy dietary and lifestyle choices work to improve your mood and the health of your gut microbiota.

The Gut-Brain Axis: In the beginning…

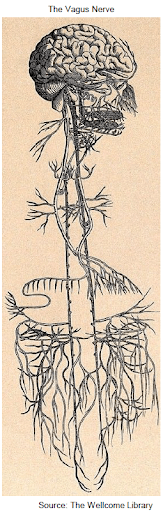

The relationship between our brains and guts has been known about for some time. The gut is linked to our brain via the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is part of the autonomic nervous system. It tells us when to breathe, digest and swallow food automatically (‘rest and digest’). The brain receives messages from our gut and the gut receives messages from the brain. For example, the brain can control how we digest our food, and the gut can control our level of hunger.

In addition, the gut has its own local nervous system operating entirely independently to the brain called the enteric nervous system (ENS). This so-called ‘second brain’ also receives signals from our brain via the vagus nerve.

So how does the actual gut microbiota influence our mood and vice versa?

In addition to vagus and enteric nerve communication, there are also other pathways via our blood stream and immune system that are driven by our gut microbiota. Together, all these methods of communication involving our gut microbiota include:

- Stress, depression and gut microbiota

- Gut microbiota derived substances

1. Stress, depression and gut microbiota

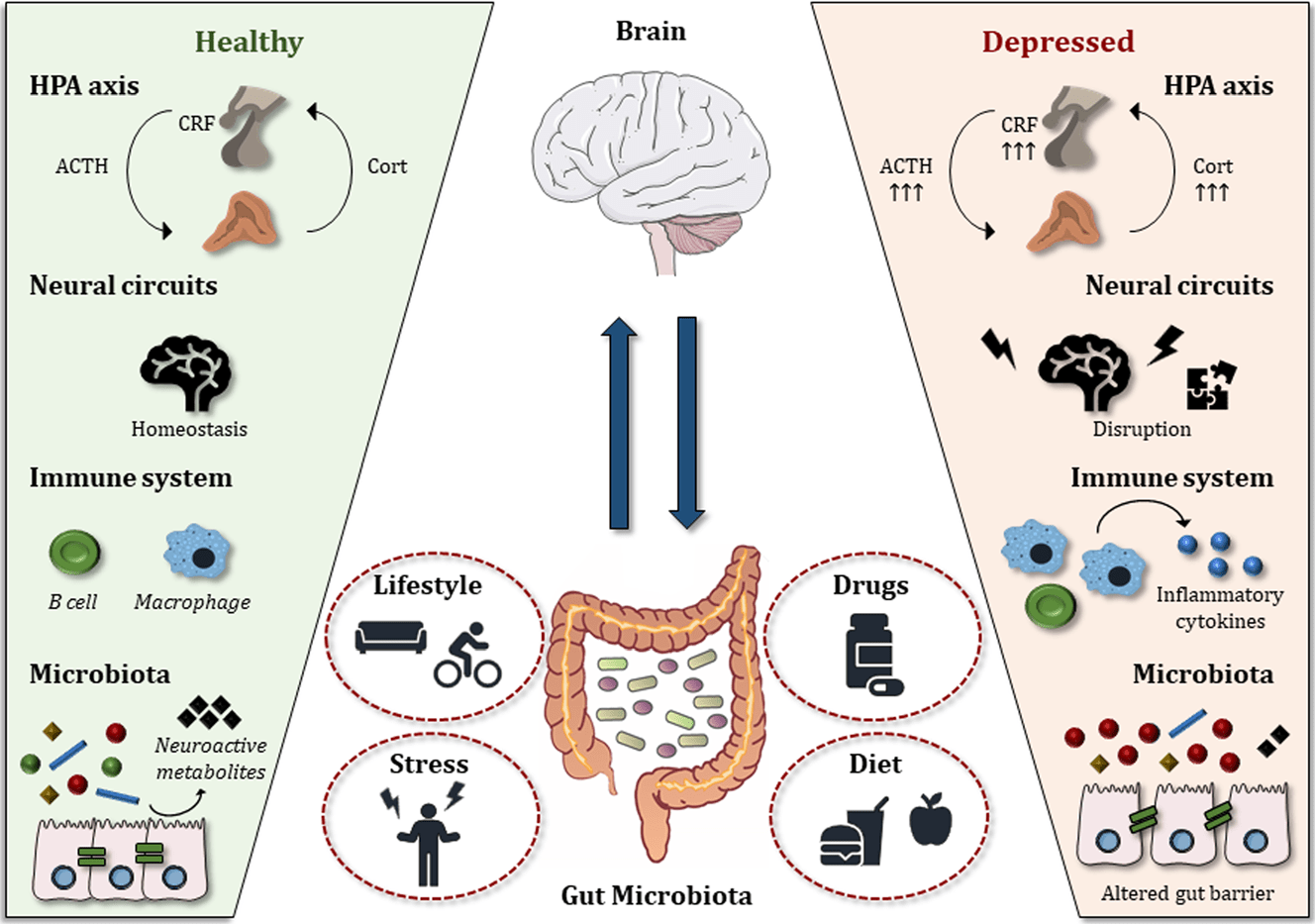

Activity of the gut bacteria can affect stress and the levels of anxiety and depression. A healthy gut ecosystem can improve your resilience to stress. An imbalance gut ecosystem can affect mental health.

The brain operates a stress response known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis (HPA) response. It is a carefully controlled system, intelligently designed to inform us of when to run in danger. In our modern lives however, this stress response often becomes overactive and dysfunctional and we find a strong link to depression and anxiety disorders.

In such overactivation, stress hormones negatively influence our immune system, driving inflammation which leads to gut wall damage and an imbalanced gut ecosystem. It is then a vicious cycle, where the imbalance in bacteria impacts mental health via similar pathways.

We could think of this ecosystem like a seesaw between the ‘good bacteria’ and the ‘bad bacteria’. When the seesaw is balanced, there is health and harmony. When the seesaw is forced to tilt under stress, the ‘bad bacteria’ are given the opportunity to rise, pushing the ‘good bacteria’ into the ditch. The body fights against the ‘bad bacteria’, the brain receives stress messages, and the resulting inflammation affects our mood.

Working to rebalance the gut ecosystem through a diverse, mainly plant based diet rich in pre and probiotics to support the level of ‘good bacteria’ may lower the stress response and improve mood.

2. Gut microbiota derived substances

Our gut bacteria produce various substances that enable communication between the gut and the brain. Examples of these substances are provided below and include fatty acids, vitamins and brain chemicals.

A reason to eat more dietary fibre?…

When we consume dietary fibre, many of our ‘good’ probiotic gut bacteria feed off and ferment this fibre into substances called short chain fatty acids (SCFA’s). An example of a SCFA is butyrate.

Butyrate and an inflamed brain…

Butyrate is the most well studied of SCFAs. It is fundamental to the maintenance of our gut cells and ultimately, the state of our mental health. This is because butyrate supports the integrity of our gut cell wall – an important barrier between the outside world and our immune system.

A large majority of our immune system resides behind our gut wall. Vital elements of the immune system include our gut wall barrier and our blood-brain barrier (BBB), the defense walls for our body and brain. The BBB protects the brain from toxins and pathogens reaching our brain cells, at the same time as selectively allowing vital nutrients to reach the brain. Our gut wall behaves in a similar fashion and is equally vulnerable to damage: you may already have heard of ‘leaky gut’.

A gut microbiota with low levels of butyrate producing ‘good bacteria’, is often associated with a ‘leaky gut’. Foreign particles that are not normally designed to pass throughout the gut wall are then exposed to the immune system and inflammation is created. ‘Leaky gut’ is often associated with a ‘leaky’ BBB, allowing these inflammatory signals to travel into the brain and affect our mood.

The good news is that we can dampen this inflammation by supporting the production of butyrate in our gut ecosystem. Our previous blog gives ideas of how to do just this through simple dietary and lifestyle modifications. Studies suggest high levels of butyrate production in the human gut is associated with higher quality of life.

Lactate and brain cell energy

Many of our beneficial microbes are called ‘Lactic Acid Bacteria’ (LAB) because upon fermentation in our gut, they produce lactate. Examples of LAB include Bifidobacterium and some lactobacillus species like lactobacillus lacti).

Lactate has antidepressant properties in animal studies, it is found to have the ability to cross our BBB and be used by our brain cells for energy as well as supporting anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Interestingly exercise has been shown to support the growth of LAB and this may in part explain why exercise can improve our mood.

Feeding the brain with essential vitamins

Up to a third of people with depression may have a vitamin B9 (Folate) deficiency. Folate is produced by ‘good’ probiotic gut bacteria such as the lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Folate can pass through the BBB and supports the production not only of serotonin (the ‘stabilising’ brain chemical), but also an important growth factor in the brain called ‘brain derived neurotrophic factor’ (BDNF). BDNF and serotonin are inversely associated with depression.

The gut-brain chemicals…

The neurotransmitter serotonin is made inside our bodies from the dietary protein tryptophan, found in foods such as poultry, eggs, nuts & seeds. Although some serotonin is made in the brain, it is now suggested that 90% of all our serotonin is produced in the gut. It is not yet clear however, as to how much of this serotonin reaches our brain. Medications such as SSRIs, (Selective Serotonergic Reuptake Inhibitors) enhance the production of serotonin in the brain.

As mentioned above, an unhealthy gut microbiota may cause an immune response, and the resulting inflammation can ‘steal’ the tryptophan by pushing it down a different pathway and preventing it from being converted to serotonin.

Furthermore, potentially ‘bad’ bacteria such as E.coli, have been shown to breakdown the protein tryptophan before it has the ability to be converted to serotonin, therefore if E.coli is a dominant species in the gut, some people may exhibit depressive behaviour.

The ‘good’ probiotic microbes, such as the lactobacillus species, have been given to animals. These studies found changes in the expression of GABA (the ‘calming’ brain chemical) and depressive-like behaviour improved. When the vagus nerve is removed, these changes did not occur, highlighting the equal significance of the vagus nerve in communication between our gut microbiota and the brain.

Conclusion

It’s complicated but the pathways in the gut-brain-axis influence our mood because of the messages the gut microbiota send to the brain cells. These bi-directional pathways between the gut and the brain means that it is difficult for the research to be clarified in clinical studies.

It is clear however, that if we can maintain a diverse, balanced and healthy gut microbiota by implementing some dietary and lifestyle changes mentioned in our previous blog, we will be positively supporting our mental health.

Our next blog will discuss even more specific dietary aspects to supporting mental health as well as the gut.

Note: There are three blogs in this series. The first blog discussed the Gut Microbiome and Mood. Find out how Eating nutrient-dense foods might improve your brain health in the third blog.

References and further reading:

Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2020; 28(1):26-39

Microorganisms. 2018 Jun; 6(2): 35.

Microb Cell. 2019 Oct 7; 6(10): 454–481.

Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2012 Oct;13(10):701-12

Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2011; v12: 453-466